- Exclusionary zoning initially started explicitly to keep minorities out of certain areas of a city.

- Once the Supreme Court struck down these explicitly racist laws, new exclusionary zoning laws were passed that were based on alleged economic principles but had the same racist effects.

- Similar laws carry through to today with zoning that limits housing and hurts affordability throughout a city.

It kind of went under the radar a little bit, but last week the White House put out a blog entry on the history of exclusionary zoning and its lasting effects. Based on how much we’ve talked about similar issues here in Texas – especially in Austin – I thought it would be good to look at exclusionary zoning this week. So that’s what we will do.

I mention this a lot, but its important to note that racist housing and zoning policy in the US is a much, much bigger topic than I have space to address in this blog. This, therefore, is just a quick, basic overview of the issue. It is not a comprehensive analysis.

Origins of Exclusionary Zoning

In the late 1800s/early 1900s cities around the US began more comprehensive planning – including setting up zoning. Unfortunately this included many areas setting up explicitly racist zoning laws. These laws would literally keep minorities out of certain areas and not allow them to live there. There would be separate, specific areas that were the only places that minorities were allowed to live. Thankfully, in 1917, the US Supreme Court ruled that explicitly racist zoning laws like this were illegal.

As a result, after that cities had to become more creative with how they enforced their racism.

The Rise of Exclusionary Zoning

Once cities were not allowed to enact explicitly racist zoning laws, they started passing other laws that looked neutral on their face but were ultimately aimed at achieving the same racist goals.

For example, in St. Louis the council enacted zoning laws designed to preserve homes in areas that were unaffordable to most Black families, and the city’s zoning commission would change an area’s zoning designation from residential to industrial if too many Black families moved in. Similarly, research on ,Seattle’s 1923 zoning laws shows that areas in which Black or Chinese-American families lived were disproportionately likely to receive commercial zoning.

,Here in Austin, the council had a city plan to isolate minorities which included a 1928 proposal to create a “Negro District” — making it the only part of the city where African-Americans could access schools and other public services.

,Most of this was done under guise of economic development. It was helped by the ,Supreme Court, which explicitly permitted zoning regulations in a 1926 case. Writing for the majority, Justice Sutherland referred to a planned apartment complex as “a mere parasite” on the neighborhood and how it would affect neighborhood property values.

I’m not going to go through the entire history of racist zoning from the 20s, but suffice it to say that it has continued in a similar way since that time.

Present Day Exclusions

And when I say it has continued – I mean it continues to this day. Here I want to be perfectly clear – I do not think that modern day proponents of exclusionary zoning are normally doing it for racist intent. Usually it is done to protect single family housing and keep a neighborhood with its current status.

This is done through putting restrictions on the type of homes that can be built in a neighborhood. For example, cities often enact zoning laws that have minimum lot size requirements, minimum square footage requirements, prohibitions on multi-family homes, parking requirements, and limits on the height of buildings. While they may not have been explicitly enacted for racist intents, they trace their lineage directly to the racist zoning of the early 20th century.

And in addition to that, these restrictions severely hurt affordability. By enacting these restrictions, a city limits the total number of housing units available in an area. As a result, there is less supply in the city. And, as any econ 101 student can tell you, the price for the available housing goes up.

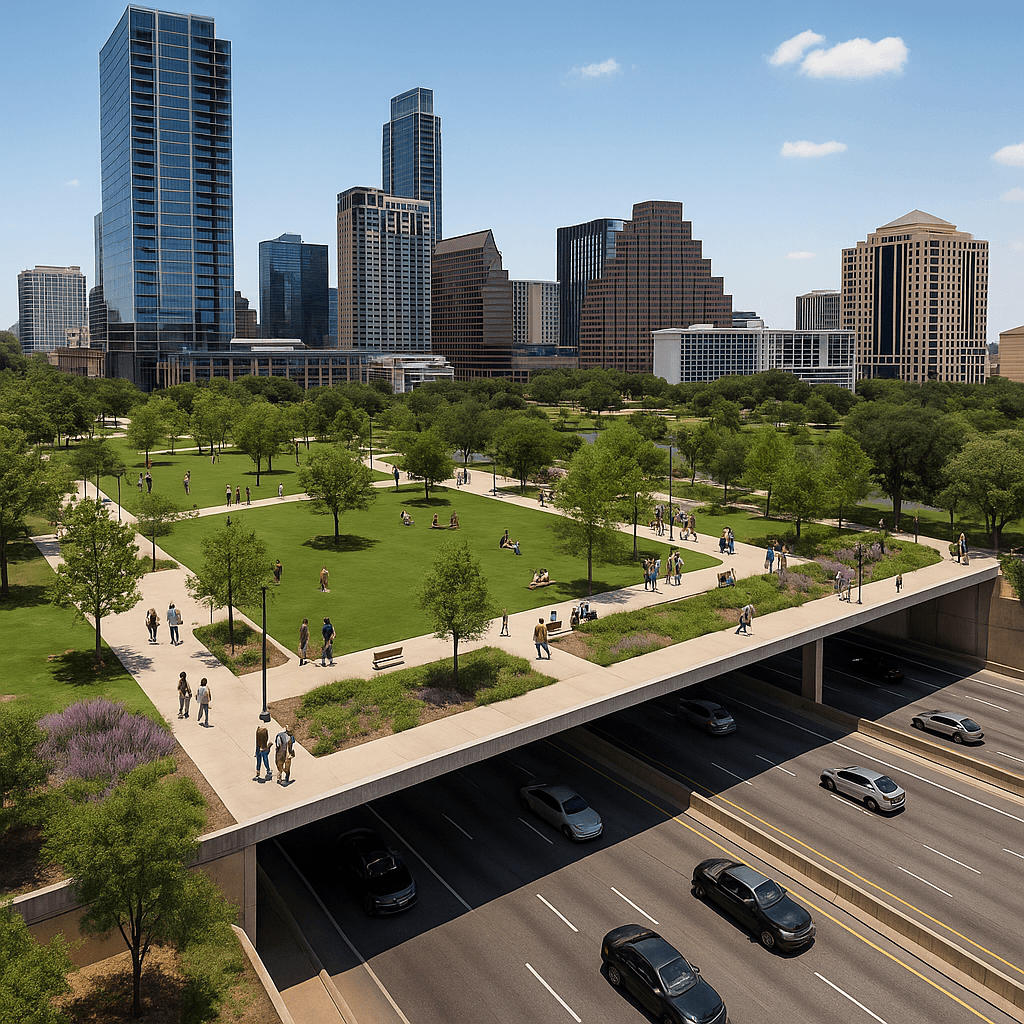

Austin is going through this exact issue now. I’ve written before about how it has tried to solve the issue with changes to its code. But now that is stuck in the courts – with no end in sight. Hopefully our leaders can get creative to get rid of some of these exclusionary zoning laws and allow higher density housing that improves access and affordability for all.